In our never-ending quest for different and varied flavors of compression, we take the plunge on a very reasonably priced all-analog, 500-series recreation of one of the most expensive compressors on the vintage market.

The Fairchild Audio model 660 compressor (and its stereo equivalent, the model 670) were introduced in the early 1950s. The 670, in particular, is considered the absolute holy grail of studio equipment. I haven’t seen pricing on one of these units in a long time, but as far back as 2003 they were rumored to sell for $30,000 on the vintage market. Even if the market has cooled somewhat since then, you’re still looking at prices resembling that of a late model used car if you’re actually in the market for one of these units.

The 660/670 are what’s known as a vari-mu compressors, a design which is unique among compressor circuits in that it uses vacuum tubes for the gain reduction circuitry, not just for the amplification path.

The 670 weighs an incredible 65 pounds, sports 14 transformers and 20 tubes, and occupies 6 rack spaces. It’s an absolutely huge unit. So even if you find yourself able to afford one, you would still need to find a pretty huge space to put it.

[blockquote blockquote_style=”boxed” align=”right” text_align=”left” cite=”” style=””]At 65 pounds, and featuring 14 transformers, there’s a lot of iron in a Fairchild 670.[/blockquote]

As a result, there’s been all sorts of attempts over the years, especially in the plugin era, to emulate the sound of the Fairchild 660/670. But the general feeling has been that while some of these emulations are good, they don’t have the “weight” of the real thing. That’s a frequent complaint about software emulations of honest-to-god, electrons-going-through-iron hardware units. And at 65 pounds, there’s an awful lot of iron in a real Fairchild 670.

Enter the two founders of Anamod: Dave Amels and Greg Gualtieri. Founded in 2006, the company brought together Amels’ background in digital modeling for Bomb Factory, a company that designed software emulations of classic gear, with Gualtieri’s background in physics and acoustic research for Bell Labs. The company introduced the AM660, a 500-series version of the Fairchild Model 660. The company is quite insistent that, despite the AM660’s small size, it is an all analog recreation of the Fairchild 660.

Reading about the analog nature of the AM660, its tiny stature, and the opportunity to dip a toe into the world of vari-mu compression, I was intrigued. So when a screaming deal on a pair of used AM660s came up on the used market, I went ahead and grabbed them.

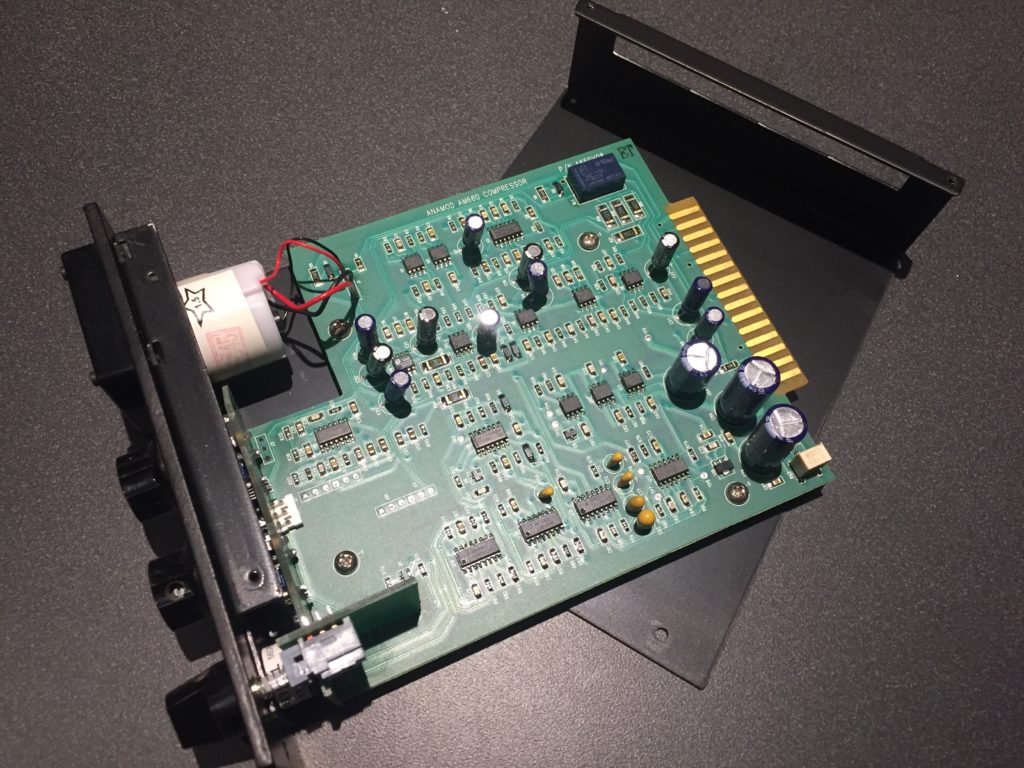

Having built plenty of 500-series gear at this point, many of which involve two solid blocks of honest-to-god transformer heft in their designs, I have to say that I was really, really taken aback by how light and insubstantial the AM660 is right out of the box. The unit consists of a single printed circuit board, thinly covered with surface-mounted components and a handful of electrolytic and tantalum capacitors.

Now, the presence of all those integrated circuits (which most people assume–incorrectly–are necessarily “digital”), does not negate the fact that the circuit path is all analog. In any case, while I personally don’t have enough experience with circuit design to really tear the unit down and see what’s going on, it’s a bit disarming to see how sparse these units are.

[blockquote blockquote_style=”boxed” align=”left” text_align=”left” cite=”” style=””]With clients in the room, there’s only so much tinkering you can do before you have to punt and get on with the session. [/blockquote]

As to how these units sound, and how true they are to the original, I think I’m going to withhold judgment on those questions until I’ve had more time to play with them in different recording scenarios. I have never encountered the real McCoy, so I don’t have that frame of reference, first of all. Second, as of this writing, I have only used them on one session thus far, a tracking session, and I really had trouble dialing in something I found useful. With clients in the room, waiting for you to hit “record,” there’s only so much tinkering you can do with a new piece of gear before you have to punt, go back to a more familiar piece of gear and process, and get on with the session. I suspect my issue is unfamiliarity with vari-mu compression in general, and not just the AnaMod 660 in general. In a review of Anamod’s stereo unit in TapeOp magazine, Joel Hamilton mentions that the tricky thing about using a Fairchild 670 is the fact that “when you hit the threshold with a 670, you see your [levels] hang out at [full level] no matter how hard you dig into it.” That’s the idea of the 660/670 — that the level stays the same no matter how hot of a signal you feed into it. Other compression schemes generally don’t work that way, so in a time crunch, I had a hard time getting what I needed. I think I’ll try it on a mix and see what I get.

More to come when I have more to report!

Share this:

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window) Email

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window) LinkedIn

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Click to print (Opens in new window) Print