Yesterday, I told you about the St. Petronille Contemporary Choir and their 1995 album, A Time Will Come For Singing — its origins, production, and legacy. Today, I’d like to tell you about my…er…non-involvement with the original project, and where we are today.

[blockquote]This is Part 3 of a series on the production of A Time Will Come For Singing (Special Edition). See All Posts[/blockquote]

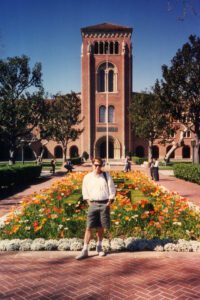

As I wrote yesterday, in the Fall of 1995, I had just left for law school at the University of Southern California (USC). Back at home in Glen Ellyn, Illinois, my good friend Paul Sirvatka and the St. Petronille Contemporary Choir had just gratefully accepted a financial gift from a couple of St. Pet’s parishioners that would send the group into the studio to record their first (and only) album.

Law school (particularly the first semester of the first year) has a reputation for being particularly rigorous, and it certainly was for me. I felt like I had my head down for most of the semester. And this being before the era of social media, I really didn’t hear too much news about what was going on back home.

Then, one day in mid-October, I was talking to my mom on the phone. She casually mentioned that Paul and the choir had decided to record a Christmas album. They had been in the studio for the past few weeks recording, with an eye towards getting the album out by Christmas of that year.

Now, regular readers of this blog will understand how crushed I was by this news. Make a recording in a real studio? When it’s finished, hear your voice coming off one of those cool, thin, silver optical discs? Even in those days, that was my kind of project! But they’d cranked it out in about three weeks, and I never heard a word about it until it was already done. Heck, I didn’t even go home for Thanksgiving that year — that’s how intense first semester of law school was — and yet, had I known the group was recording, I would have found a way to get home for at least a few days. At least long enough to contribute to the project in some fashion.

But time was of the essence, so I didn’t get that chance. The album was produced in 3 weeks, pressed and available for Christmas. It quickly sold out, Paul resigned from the group a few months later, and the album was never restocked. Those who had a copy on CD enjoyed breaking it out every Christmastime, but that was about it.

Over the years, while I always enjoyed the album very much, I was always a little sad. Why? Because I wanted to be on that project! It gnawed at me that had I just been in the right place at the right time, I could have been part of it, too. When I started getting into recording recreationally around 1999, I used to tell Paul that I was thinking about making my own, personal remix of the album where I would simply just (subtly!) add myself to the tenor parts, and pretend I’d been on the project all along.

Later, when iTunes appeared on the scene in 2003, I would occasionally get questions from friends, family or former choir members asking if the album would ever be on iTunes. I always grimaced a bit at these kinds of questions, seeing as I wasn’t actually on the album, but I understood why they were asking me. It’s not particularly hard to get an album up online, and I had lots of experience doing it for The SoCal VoCals and News At Eleven. But I never felt like this was my problem to solve. Having not been on the original project, I always had to defer to Paul on this question — let me know if this is something you’d like to do, and I will make it happen.

Paul, meanwhile, was always very dismissive of the idea that the album would ever go online. Why? Two main reasons, I think. One, the album was thrown together very quickly–over the course of a three week sprint–and Paul could always point to all sorts of flaws (especially in his own performances) which might be minor to other listeners, but which drove him absolutely nuts. As a performer, it’s just different listening to your own work; I readily understand this. Two, within a few years after the album came out, synthesizer and sampling technology had improved to the point that the album just sounded hopelessly dated.

As I mentioned yesterday, the bulk of the instrumentation on the original album came out of a single sound module — a Korg M-1R. If someone in the group didn’t play a particular instrument, you just called on your one magic synth box to step up and fill the void.

Some of the amazing cornucopia of sounds you could get out of a sound module like the M-1R might be pretty good. Other sounds were incredibly bland by today’s standards — hampered by the challenge of trying to offer “one size fits all” sounds for any conceivable genre of music, to say nothing of the challenge of how to reproduce a complex waveform with only a couple of megabytes of memory. Still, what mattered in those days was that even if you didn’t have the budget to hire a bunch of musicians to play all the instruments you needed, you could get what seemed like perfectly reasonable facsimiles! of those sounds from the one keyboard or sound module you happened to own. At the time, just having access to all those sounds was amazing, even if they weren’t particularly faithful to the “real” sound of the instrument. On an absolute shoestring budget, you could put together something resembling the sound of a full band.

What I don’t think anyone could appreciate at the time, as memory got exponentially cheaper and sampling technology radically improved, was how dated this approach would sound just a few years later.

With that in mind, over the years Paul always blanched when I suggested that we make the album available on iTunes. He felt it was just too dated sounding; while it was a fun little project for the choir, no one would ever take it seriously today. Nevertheless, around 2007, Paul mentioned that he still had the 2-inch, 24-track master tapes sitting in a closet at his house in Glen Ellyn. Since analog tape is very delicate and does not improve with age, I suggested that we go ahead and pay to get the tapes professionally transferred to 96K digital. We had no particular plans to do anything with them, but maybe someday we would. It sat on my hard drive for a long time.

Fast forward to this Spring. When Paul came to visit in March, we dusted off the hard drives and listened to some of the 24-track masters from A Time Will Come For Singing. Paul winced, as he always did, at any number of dated sounding elements he heard. Nothing had really changed in that regard. But we both agreed that the “real” aspects of the album — the vocal performances, piano, and guitars — actually sounded really good when you stripped away all the synthesized junk from 1995.

Over several late nights with a reasonable quantity of good wine, we began to discuss the possibility of picking a song from the album for a digital makeover. We’d replace the cheesy synth patches with modern samples or real performances, clean up the rough edges, and release it as a single. The most obvious candidate was Paul’s original song “Here I Am, O Lord.” The song had been performed many times over the years by various groups I’ve been associated with. We even recorded it with News At Eleven on our debut album, Have You Not Heard?, in 1999. Paul liked the idea that perhaps we could replace the dated-sounding elements — particularly the canned drums and bass guitar — with real versions performed live in the studio.

But something else we did that week really caught Paul’s ear. I demonstrated for him a few of the really incredible ways in which digital audio technology has improved in just the past few years. Sampling has radically improved since 1995, obviously, but in the past 10 years or so, you can now have at your fingertips an incredible collection of hyper-realistic “virtual instruments” consisting of hundreds or thousands of gigabytes of individual samples. We’re to the point today where it’s getting difficult or impossible to tell you’re listening to a sampled performance — particularly in a full mix.

As for those little performance flaws, we’ve all become familiar with the ability to tune solo singers and instruments with plugins such as Auto-Tune. That technology has been available since the late 90s — a technology Cher and her producers memorably abused, for fun and profit, on her 1998 hit, “Believe”. But newer software such as Melodyne allows you to not only tune a solo voice or instrument, but individual singers or instruments in a group recording. Got a great performance, except for that one singer that really missed a note? That piano chord in the second verse should really have been a minor chord, not a major one? We can fix that now.

Take those sorts of advances — and of course, the ease of editing and mixing in the digital audio workstation era, where there is no practical limit on the number of tracks you can have in your session — and a picture of what we might be able to do with the 1995 source material began to emerge. Rather than re-release just a single or two, we started talking about the possibility of re-releasing the entire album. No more wincing at those little mistakes that found their way to tape in the rush to get the project out in time for Christmas. No more cringing at the sound of a canned, cheesy “synth pad” sound on a classical track when we can have the sound of a honest-to-God symphonic string section.

By the time Paul left at the end of his week-long visit in March, our plans were starting to crystallize. I would get to work on cleaning up those elements of the original tracks we were going to keep. Paul would make a phone call to his friend, Steve Linley, an accomplished drummer from Austin, TX, to invite him to come record with us. We’d plan on re-convening later in the Summer, with an eye towards hopefully finishing this project in time for Christmas 2017.

Paul and Steve are arriving tomorrow. The drum kit is set up in ISO 2b, mic’d up and ready to rock!

Share this:

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window) Email

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window) LinkedIn

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Click to print (Opens in new window) Print